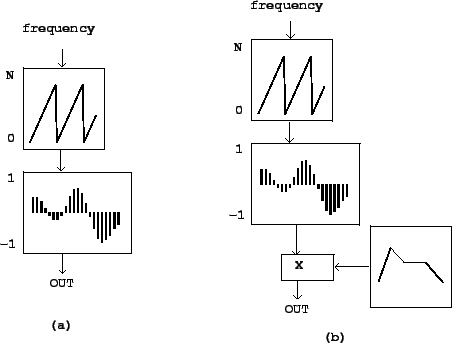

Figure 2.2 suggests an easy way to synthesize any desired fixed

waveform at any desired frequency, using the block diagram shown in Figure

2.3. The upper block is an oscillator--not the sinusoidal

oscillator we saw earlier, but one which produces sawtooth waves instead. The

output values, as indicated at the left of the block, should range from

![]() to the wavetable size

to the wavetable size ![]() . This is used as an index into the

wavetable lookup block (introduced in Figure 2.1), resulting,

as shown in Figure 2.2(b,c), in a periodic waveform.

Figure 2.3(b) adds an envelope generator and a multiplier

to control the output amplitude in the same

way as for the sinusoidal oscillator shown in Chapter 1. Often, one uses

a wavetable with (RMS or peak) amplitude 1, so that the amplitude of the

output is just the magnitude of the envelope generator's output.

. This is used as an index into the

wavetable lookup block (introduced in Figure 2.1), resulting,

as shown in Figure 2.2(b,c), in a periodic waveform.

Figure 2.3(b) adds an envelope generator and a multiplier

to control the output amplitude in the same

way as for the sinusoidal oscillator shown in Chapter 1. Often, one uses

a wavetable with (RMS or peak) amplitude 1, so that the amplitude of the

output is just the magnitude of the envelope generator's output.

|

Wavetable oscillators are often used to synthesize sounds with specified,

static spectra. To do this, you can precompute ![]() samples of any waveform

of period

samples of any waveform

of period ![]() (angular frequency

(angular frequency ![]() ) by adding up the elements of the

FOURIER SERIES (section 1.7). The computation involved in

setting up the wavetable at first might be significant, but this may be done

in advance of the synthesis process, which can then take place in real time.

Frequently, wavetables are prepared in advance and stored in files to be

loaded into memory as needed for performance.

) by adding up the elements of the

FOURIER SERIES (section 1.7). The computation involved in

setting up the wavetable at first might be significant, but this may be done

in advance of the synthesis process, which can then take place in real time.

Frequently, wavetables are prepared in advance and stored in files to be

loaded into memory as needed for performance.

While direct additive synthesis of complex waveforms, as shown in Chapter 1,

is in principle infinitely flexible as a technique for producing time-varying

timbres, wavetable synthesis is much less expensive in terms of computation

but requires switching wavetables to change the timbre. An intermediate

technique, more flexible and expensive than simple wavetable synthesis but

less flexible and less expensive than additive synthesis, is to create

time-varying mixtures between a small number of fixed wavetables. If the

number of wavetables is only two, this is in effect a cross-fade between

the two waveforms, as diagrammed in figure 2.3. Here we suppose

that some signal

![]() is to control the relative strengths of the two

waveforms, so that, if

is to control the relative strengths of the two

waveforms, so that, if ![]() , we get the first one and if

, we get the first one and if ![]() we

get the second. Supposing the two signals to be cross-faded are

we

get the second. Supposing the two signals to be cross-faded are ![]() and

and

![]() , we compute the signal

, we compute the signal

In using this technique to cross-fade between wavetable oscillators, it might be desirable to keep the phases of corresponding partials the same across the wavetables, so that their amplitudes combine additively when they are mixed. On the other hand, if arbitrary wavetables are used (for instance, borrowed from a recorded sound) there will be a phasing effect as the different waveforms are mixed.

This scheme can be extended in a daisy chain to travel a continuous path between a succession of timbers. Alternatively, or in combination with daisy-chaining, cross-fading may be used to interpolate between two different timbres, for example as a function of musical dynamic. To do this you would prepare two or even several waveforms of a single synthetic voice played at different dynamics. and interpolate between successive ones as a function of the output dynamic you want.

You can even use pre-recorded instrumental (or other) sounds as a waveform. In its simplest form this is called "sampling" and is the subject of the next section.