|

Control computations may come from a variety of sources, both internal and external to the overall computation. Examples of internally engendered control computations include sequencing (in which control computations must take place at pre-determined times) or feature detection of the audio output (for instance, watching for zero crossings in a signal). Externally engendered ones may come from input devices such as MIDI controllers, the mouse and keyboard, network packets, and so on. In any case, control computations may occur at irregular intervals, unlike audio samples which correspond to a steadily ticking sample clock.

We will need a way of describing how information

flows between control and audio computations, which we will base on the

notion of a

control stream.

This is simply a collection of numbers--possibly empty--that appear as a result of control

computations, whether

regularly or irregularly spaced in logical time.

The simplest possible control stream has no information other than a

time sequence:

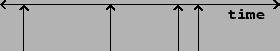

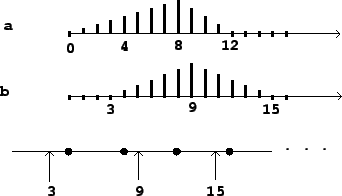

Control streams may be shown graphically as in Figure 3.3. A number line shows time and a sequence of arrows points to the times associated with each event. The control stream shown has no data (it is a time sequence). If we want to show data in the control stream we will write it at the base of each arrow.

A

numeric control stream

is one that contains one number per time point, so that it

appears as a sequence of

ordered pairs:

A numeric control stream is roughly analogous to a ``MIDI controller", whose values change irregularly, for example when a physical control is moved by a performer. Other control stream sources may have higher possible rates of change and/or more precision. On the other hand, a time sequence might be a sequence of pedal hits, which (MIDI implementation notwithstanding) shouldn't be considered as having values, just times.

Numeric control streams are like audio signals in that both are just time-varying numeric values. But whereas the audio signal comes at a steady rate (and so the time values need not be specified per sample), the control stream comes unpredictably--perhaps evenly, perhaps unevenly, perhaps never.

Let us now look at what happens when we try to convert a numeric

control stream to

an audio signal. As before we'll choose a block size ![]() . We will consider

as a control stream a square wave of period 5.5:

. We will consider

as a control stream a square wave of period 5.5:

Fast-as-possible conversion is most appropriate for control streams which do

not change frequently compared to the block size. Its main advantages are

simplicity of computation and the fastest possible response to changes. As the

figure shows, when the control stream's updates are too fast (on the order of

the block size), the audio signal may not be a good likeness of the sporadic

one. (If, as in this case, the control stream comes at regular intervals of

time, we can use the sampling theorem to analyze the result. Here the Nyquist

frequency associated with the block rate ![]() is lower than the input square

wave's frequency, and so the output is aliased to a new frequency lower than

the Nyquist frequency.)

is lower than the input square

wave's frequency, and so the output is aliased to a new frequency lower than

the Nyquist frequency.)

|

Part (b) shows the result of nearest-sample conversion. Each new value of the

control stream at a time ![]() affects output samples starting from index

affects output samples starting from index

![]() (one more than the greatest integer not exceeding

(one more than the greatest integer not exceeding ![]() ).

This is equivalent to using fast-as-possible conversion at a block size of 1;

in other words, nearest-sample conversion hides the effect of the larger block

size. This is better than fast-as-possible conversion in cases where the

control stream might change quickly.

).

This is equivalent to using fast-as-possible conversion at a block size of 1;

in other words, nearest-sample conversion hides the effect of the larger block

size. This is better than fast-as-possible conversion in cases where the

control stream might change quickly.

Part (c) shows sporadic-to-audio conversion, again at the nearest sample,

but now also using two-point interpolation to further increase the time

accuracy. Conceptually we can describe this as follows. Suppose the value

of the control stream was last equal to ![]() , and that the next point is

, and that the next point is

![]() , where

, where ![]() is an integer and

is an integer and ![]() is the fractional part of the

time value (so

is the fractional part of the

time value (so ![]() ). The first point affected in the audio

output will be the sample at index

). The first point affected in the audio

output will be the sample at index ![]() . But instead of setting the output

to

. But instead of setting the output

to ![]() as before, we set it to

as before, we set it to

Numeric control streams may also be converted to audio signals using ramp functions to smooth discontinuities. This is often used when a control stream is used to control an amplitude, as described in Section 1.5. In general there are three values to specify to set a ramp function in motion: a start time and target value (specified by the control stream) and a target time, often expressed as a delay after the start time.

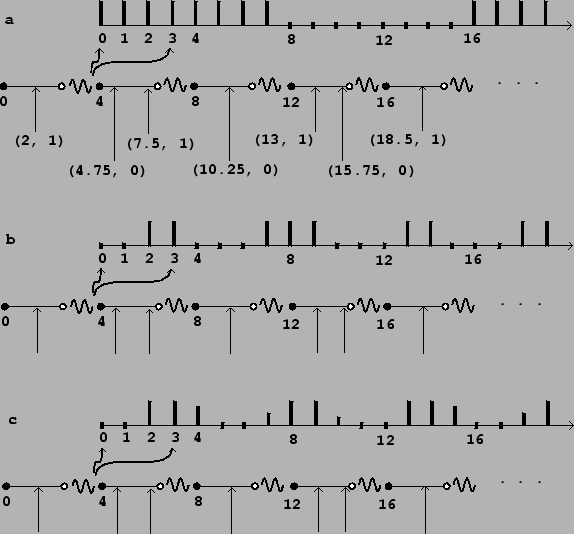

In such situations it is almost always accurate enough to adjust the start and

ending times to match the first audio sample computed at a later logical time,

a choice which corresponds to the fast-as-possible scenario above. Figure

3.5 (part a) shows the effect of ramping from 0, starting at

time 3, to a value of 1 at time 9, immediately starting back toward 0 at

time 15, with block size ![]() . The times 3, 9, and 15 are truncated to

0, 8, and 12, respectively.

. The times 3, 9, and 15 are truncated to

0, 8, and 12, respectively.

|

In real situations the block size might be on the order of a millisecond, and adjusting ramp endpoints to block boundaries works fine for controlling amplitudes; reaching a target a fraction of a millisecond early or late rarely makes an audible difference. However, other uses of ramps are more sensitive to time quantization of endpoints. For example, if we wish to do something repetitively every few milliseconds, the variation in segment lengths will make for an audible aperiodicity.

For situations such as these, we can improve the ramp generation algorithm to start and stop at arbitrary samples, as shown in Figure 3.5 (part b), for example. Here the endpoints of the line segments line up exactly with the requested samples 3, 9, and 15. We can go even further and adjust for fractional samples, making the line segments touch the values 0 and 1 at exactly specifiable points on a number line.

For example, suppose we want to repeat a recorded sound out of a wavetable 100 times per second, every 441 samples at the usual sample rate. Rounding errors due to blocking at 64-sample boundaries could detune the playback by as much as a whole tone in pitch; and even rounding to one-sample boundaries could introduce variations up to about 0.2%, or three cents. This situation would call for sub-sample accuracy in sporadic-to-audio conversion.