The examples for this chapter will use Pd's abstraction mechanism, which permits the building of patches that may be reused any number of times. One or more object boxes in a Pd patch may be subpatches, which are separate patches encapsulated inside the boxes. These come in two types: one-off subpatches and abstractions. In either case the subpatch appears as an object box in the parent patch.

If you type ``pd" or ``pd my-name" into an object box, this creates a one-off subpatch. The contents of the subpatch are saved as part of the parent patch, in one file. If you make several copies of a subpatch you may change them individually. On the other hand, you can invoke an abstraction by typing into the box the name of a Pd patch saved to a file (without the ``.pd" extension). In this situation Pd will read that file into the subpatch. In this way, changes to the file propagate everywhere the abstraction is invoked.

Object boxes in the subpatch (either one-off or abstractions) may create inlets and outlets on the box in the parent patch. This is done with the following classes of objects:

![]() ,

,

![]() :

create inlets for the object box containing the subpatch. The

:

create inlets for the object box containing the subpatch. The

![]() version creates an inlet for audio signals, whereas

version creates an inlet for audio signals, whereas

![]() creates one for control streams. In either case, whatever

shows up on the inlet of the box in the parent patch comes out of the

creates one for control streams. In either case, whatever

shows up on the inlet of the box in the parent patch comes out of the

![]() object in the subpatch.

object in the subpatch.

![]() ,

,

![]() :

Corresponding objects for output from subpatches.

:

Corresponding objects for output from subpatches.

Pd provides an argument-passing mechanism so that you can parametrize different

invocations of an abstraction. If in an object box you type ``$1",

it is expanded to mean ``the first creation argument in my box on the

parent patch", and similarly for ``$2" and so on. The text in

an object box is interpreted at the time the box is created, unlike the

text in a message box. In message boxes, the same ``$1" means ``the

first argument of the message I just received" and is interpreted whenever

a new message comes in.

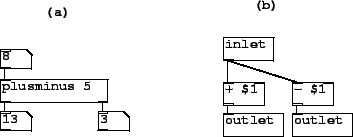

An example of an abstraction, using inlets, outlets, and parametrization, is

shown in figure 4.11. In part (a), a patch invokes ``plusminus"

in an object box, with a creation argument equal to 5. The number 8 is fed to

the

![]() object, and out comes the sum and difference of 8

and 5.

object, and out comes the sum and difference of 8

and 5.

|

The

![]() object is not defined by Pd, but is rather defined

by the patch residing in the file named ``plusminus.pd". This patch is shown

in part (b) of the figure. The one

object is not defined by Pd, but is rather defined

by the patch residing in the file named ``plusminus.pd". This patch is shown

in part (b) of the figure. The one

![]() and

two

and

two

![]() objects correspond to the inlets and outlets of

the

objects correspond to the inlets and outlets of

the

![]() object. The two ``

object. The two ``$1 arguments (to the

![]() and

and ![]() objects) are replaced by 5 (the creation argument of the

objects) are replaced by 5 (the creation argument of the

![]() object).

object).

We have already seen one abstraction in the examples: the

![]() object introduced in chapter 1, Figure 1.9(c). This shows an

additional feature of abstractions, that they may display controls as part

of their boxes on the parent patch; see the Pd documentation for a description

of this feature.

object introduced in chapter 1, Figure 1.9(c). This shows an

additional feature of abstractions, that they may display controls as part

of their boxes on the parent patch; see the Pd documentation for a description

of this feature.