|

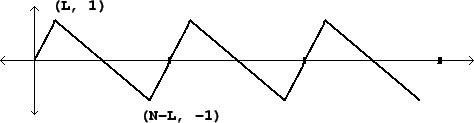

A general, non-symmetric triangle wave appears in Figure 10.7. Here

we have arranged the cycle so that, first, the DC component is zero (so that

the two corners have equal and opposite heights), and second, so that the

midpoint of the shorter segment goes through the point ![]() .

.

The two line segments have slopes equal to ![]() and

and ![]() , so the

decomposition into component parabolic waves is given by:

, so the

decomposition into component parabolic waves is given by:

The most general way of dealing with linear combinations of elementary

(parabolic and/or sawtooth) waves is to go back to the complex Fourier

series, as

we did in finding the series for the elementary waves themselves. But in this

particular case we can use a trigonometric identity to avoid the extra work of

converting back and forth. Just plug in the real-valued Fourier series:

Figure 10.8 shows the partial strengths with ![]() set to

0.03; here, our prediction is that the

set to

0.03; here, our prediction is that the ![]() dependence should extend to

dependence should extend to

![]() , in rough agreement with the figure.

, in rough agreement with the figure.

Another way to see why the partials should behave as ![]() for low values of

for low values of

![]() and

and ![]() thereafter, is to compare the period of a given partial with

the length of the short segment,

thereafter, is to compare the period of a given partial with

the length of the short segment, ![]() . For partials numbering less than

. For partials numbering less than

![]() , the period is at least twice the length of the short segment, and at

that scale the waveform is nearly indistinguishable from a sawtooth wave.

For partials numbering in excess of

, the period is at least twice the length of the short segment, and at

that scale the waveform is nearly indistinguishable from a sawtooth wave.

For partials numbering in excess of ![]() , the two corners of the triangle

wave are at least one period apart, and at these higher frequencies the two

corners (each with

, the two corners of the triangle

wave are at least one period apart, and at these higher frequencies the two

corners (each with ![]() frequency dependence) are resolved from each

other. In the figure, the notch at partial 17 occurs at the wavelength

frequency dependence) are resolved from each

other. In the figure, the notch at partial 17 occurs at the wavelength

![]() , at which wavelength the two corners are one cycle apart;

since the corners are opposite in sign they cancel each other.

, at which wavelength the two corners are one cycle apart;

since the corners are opposite in sign they cancel each other.