We have been routinely adding audio signals together, and multiplying them by slowly-varying signals (used as amplitude envelopes for example) since chapter 1. In order to complete our understanding of the algebra of audio signals we now consider the situation where we multiply two audio signals neither of which may be assumed to change slowly. The key to understanding what happens is the:

We can use this formula to see what happens when we multiply two SINUSOIDS

(page ![]() ):

):

This gives us a very easy to use tool for shifting the component frequencies of a sound, which is called ring modulation, which is shown in its simplest form in Figure 5.2. An oscillator provides the modulating signal, which is simply multiplied by the input. The term ``ring modulation" is used more generally to mean multiplying any two signals together, but here we'll just consider using a sinusoidal modulating signal.

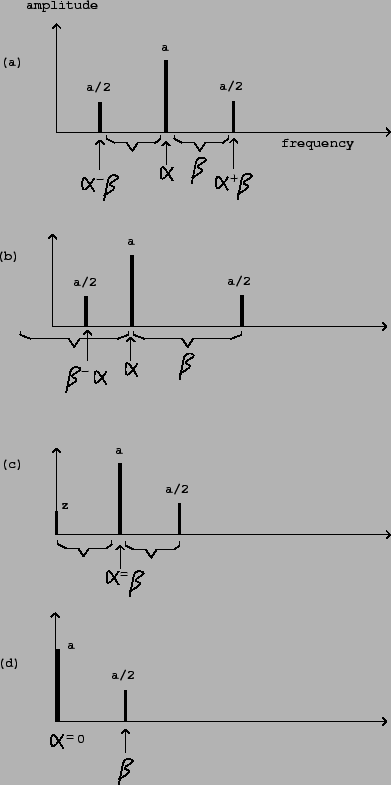

Figure 5.3 shows the result of multiplying a sinusoid of angular

frequency ![]() and amplitude

and amplitude ![]() , by another of angular frequency

, by another of angular frequency ![]() and amplitude 1:

and amplitude 1:

|

In the special case where

![]() , the second (difference) sideband

has zero frequency and its amplitude depends on the relative phases of the

two multiplicands. In this case we replace

, the second (difference) sideband

has zero frequency and its amplitude depends on the relative phases of the

two multiplicands. In this case we replace ![]() by

by ![]() in the

product formula to get:

in the

product formula to get:

We can use the distributive rule for multiplication to find out what

happens when we multiply signals together which consist of more than one

partial each. For example, in the situation above we can replace the

signal of frequency ![]() with a sum of several sinusoids:

with a sum of several sinusoids:

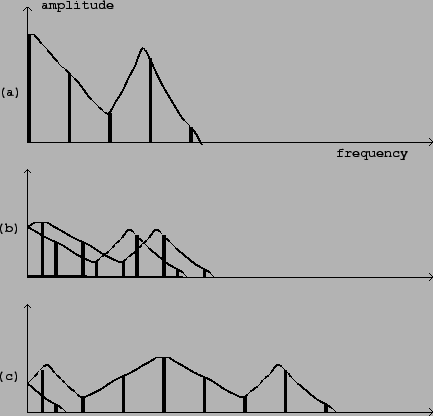

Figure 5.4 shows the result of multiplying a complex periodic signal

(with several components tuned in the ratio 0:1:2:![]() ) by a

sinusoid. Both the spectral envelope and the component frequencies of the

result transform by relatively simple rules.

) by a

sinusoid. Both the spectral envelope and the component frequencies of the

result transform by relatively simple rules.

|

The resulting spectrum is essentially the original spectrum combined with its reflection about the vertical axis. This combined spectrum is then shifted to the right by the modulating frequency. Finally, if any components of the shifted spectrum are still left of the vertical axis, they are reflected about it to make positive frequencies again.

In part (b) of the figure, the modulating frequency (the frequency of the sinusoid) is below the fundamental frequency of the complex signal. In this case teh amount of shifting is small, so that re-folding the spectrum at the end almost places the two halves on top of each other. The result is a spectral envelope roughly the same as the original (although half as high) and a spectrum twice as dense.

A special case, not shown, is modulation by a frequency exactly half the

fundamental. In this case, pairs of partials will fall on top of each other,

and will have the ratios 1/2 : 3/2 : 5/2 :![]() - an odd-partial-only signal

an octave below the original. This is a very simple and effective octave divider

for a harmonic signal, asuming you know or can find its fundamental frequency.

If you want even partials as well as odd ones (for the octave-down signal),

simply mix the original signal with the modulated one.

- an odd-partial-only signal

an octave below the original. This is a very simple and effective octave divider

for a harmonic signal, asuming you know or can find its fundamental frequency.

If you want even partials as well as odd ones (for the octave-down signal),

simply mix the original signal with the modulated one.

Part (c) of the figure shows the effect of using a modulating frequency much higher than the fundamental frequency of the complex signal. Here the unfolding effect is much more clearly visible (only one partial, the leftmost one, had to be reflected to make its frequency positive.) The spectral envelope is now widely displaced from the original; this displacement is a more strongly audible effect than the relocation of partials.

In another special case, the modulating frequency may be a multiple of the fundamental of the complex periodic signal; in this case the partials all land back on other partials of the same fundamental, and the only effect is the shift in spectral envelope.