Patch E08.phase.mod.pd, shown in Figure 5.15, shows how true frequency

modulation (part a) differs from phase modulation (shown in part b). To

accomplish phase modulation, the carrier oscillator is split into its phase and

cosine lookup components. The signal is of the form

We can predict the spectrum by expanding the outer cosine:

|

Although FM is thus just a form of ring modulated waveshaping, a confusing name change has taken place: it is FM's carrier frequency that appears as the ring modulation frequency. Keeping this in mind, we can use the strategies described in section 5.2 to generate particular combinations of frequencies. For example, if the FM carrier frequency is half the FM modulation frequency, you get a sound with odd harmonics exactly as in the octave dividing example (5.5.2).

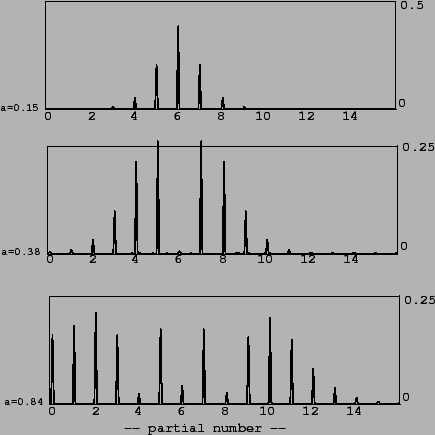

Returning to the spectra shown in Figure 5.16, we can imagine superposing several of these (sharing a fundamental (modulating) frequency but with carriers tuned to different harmonics) to build designer spectra with energy peaks, called formants, at chosen locations, imitating the production of the human voice. This was used to great effect by Chowning [Cho89] in his piece, Phoné.

Frequency modulation need not be restricted to purely sinusoidal carrier or

modulation oscillators. One well-trodden path is to effect phase modulation

on the FM spectrum itself. There are then two indices of modulation (call

them ![]() and

and ![]() ) and two frequencies of modulation (

) and two frequencies of modulation (![]() and

and ![]() )

and the waveform is:

)

and the waveform is:

Since early times [Sch77] researchers have sought combinations of phases, frequencies, and indices that manage to imitate familiar instrumental sounds; this became a major industry with the introduction of the Yamaha DX7 synthesizer.