Next: Time shifts and phase

Up: Complex numbers

Previous: Complex numbers

Contents

Index

Recall the formula for a (real-valued) sinusoid from page

![[*]](file:/usr/local/share/lib/latex2html/icons/crossref.png) :

:

This is a sequence of cosines of angles (called phases) which increase

arithmetically

with the sample number  . The cosines are all adjusted by the factor

. The cosines are all adjusted by the factor  .

We can now re-write this as the real part of a much simpler and easier to

manipulate sequence of complex numbers, by using the properties of their

arguments and magnitudes.

.

We can now re-write this as the real part of a much simpler and easier to

manipulate sequence of complex numbers, by using the properties of their

arguments and magnitudes.

Suppose that our complex number  happens to have magnitude one, so that

it can be written as:

happens to have magnitude one, so that

it can be written as:

Then for any integer  , the number

, the number  must have magnitude one as well

(because magnitudes multiply) and argument

must have magnitude one as well

(because magnitudes multiply) and argument  (because arguments add).

So,

(because arguments add).

So,

This is also true for negative values of  , so for example,

, so for example,

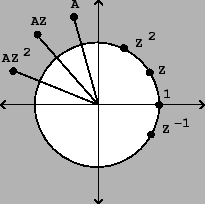

Figure 7.2 shows graphically how the powers of  wrap around

the unit circle, which is the set of all complex numbers of magnitude one.

They form a geometric sequence:

wrap around

the unit circle, which is the set of all complex numbers of magnitude one.

They form a geometric sequence:

and taking the real part of each term we get a real sinusoid with

initial phase zero and amplitude one:

The sequence of complex numbers is much easier to manipulate algebraically

than the sequence of cosines.

Figure 7.2:

The powers of a complex number  with

with  , and the same

sequence multiplied by a constant

, and the same

sequence multiplied by a constant  .

.

|

Furthermore, suppose we multiply the elements of the sequence by some (complex)

constant  with magnitude

with magnitude  and argument

and argument  . This gives

. This gives

The magnitudes are all  and the argument of the

and the argument of the  th term is

th term is

, so the sequence is equal to

, so the sequence is equal to

and so the real part is just the real-valued sinusoid:

The complex amplitude  encodes both the amplitude (equal to its magnitude

encodes both the amplitude (equal to its magnitude  )

and the inital phase (its argument

)

and the inital phase (its argument  ); the unit-magnitude complex

number

); the unit-magnitude complex

number  controls the frequency which is just its argument

controls the frequency which is just its argument  .

.

Figure 7.2 also shows the sequence

;

in effect this is the same sequence as

;

in effect this is the same sequence as

, but amplified and

rotated according to the amplitude and initial phase. In a complex

sinusoid of this form,

, but amplified and

rotated according to the amplitude and initial phase. In a complex

sinusoid of this form,  is called the

complex amplitude.

is called the

complex amplitude.

Using complex numbers to represent the amplitudes and phases of sinusoids

can clarify manipulations that otherwise might seem unmotivated. For instance,

in Section ![[*]](file:/usr/local/share/lib/latex2html/icons/crossref.png) we looked at the sum of two sinusoids with

the same frequency. In the language of this chapter, we let the two

sinusoids be written as:

we looked at the sum of two sinusoids with

the same frequency. In the language of this chapter, we let the two

sinusoids be written as:

where  and

and  encode the phases and amplitudes of the two signals.

The sum is then equal to:

encode the phases and amplitudes of the two signals.

The sum is then equal to:

which is a sinusoid whose amplitude equals  and whose phase equals

and whose phase equals

. This is clearly a much easier way to manipulate amplitudes

and phases than using series of sines and cosines. Eventually, of course,

we will take the real part of the result; this can usually be left to the

very last step of the calculation.

. This is clearly a much easier way to manipulate amplitudes

and phases than using series of sines and cosines. Eventually, of course,

we will take the real part of the result; this can usually be left to the

very last step of the calculation.

Next: Time shifts and phase

Up: Complex numbers

Previous: Complex numbers

Contents

Index

Miller Puckette

2006-03-03

![]() :

:

![]() happens to have magnitude one, so that

it can be written as:

happens to have magnitude one, so that

it can be written as:

![]() with magnitude

with magnitude ![]() and argument

and argument ![]() . This gives

. This gives

![]() ;

in effect this is the same sequence as

;

in effect this is the same sequence as

![]() , but amplified and

rotated according to the amplitude and initial phase. In a complex

sinusoid of this form,

, but amplified and

rotated according to the amplitude and initial phase. In a complex

sinusoid of this form, ![]() is called the

complex amplitude.

is called the

complex amplitude.

![]() we looked at the sum of two sinusoids with

the same frequency. In the language of this chapter, we let the two

sinusoids be written as:

we looked at the sum of two sinusoids with

the same frequency. In the language of this chapter, we let the two

sinusoids be written as: